Look at that face! Wrinkles, lots and lots of wrinkles and they couldn’t be cuter! The Shar-Pei dog breed was originally bred as a general working farm dog. The wrinkles allowed the dog to defend itself from attack because the loose skin makes it difficult to get a good grip on a Shar-Pei. But that wrinkling gene came with an unexpected rare genetic disease – one that is similar to what you or a family member may have – a recurrent fever syndrome (autoinflammatory disease)! It’s known as Shar-Pei autoinflammatory disorder (SPAID) or familial Shar-Pei fever (FSF). So far, this particular genetic disorder has only been found in dogs, but this disease affects Shar-Peis similarly to autoinflammatory diseases in humans.

Look at that face! Wrinkles, lots and lots of wrinkles and they couldn’t be cuter! The Shar-Pei dog breed was originally bred as a general working farm dog. The wrinkles allowed the dog to defend itself from attack because the loose skin makes it difficult to get a good grip on a Shar-Pei. But that wrinkling gene came with an unexpected rare genetic disease – one that is similar to what you or a family member may have – a recurrent fever syndrome (autoinflammatory disease)! It’s known as Shar-Pei autoinflammatory disorder (SPAID) or familial Shar-Pei fever (FSF). So far, this particular genetic disorder has only been found in dogs, but this disease affects Shar-Peis similarly to autoinflammatory diseases in humans.

Those with familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) in particular will understand the suffering of the Shar-Pei who suffers from FSF, because the fevers are short, but intense with a very similar presentation as FMF. Veterinarian, and the autoinflammatory expert of the dog world, Jeff Vidt reports that, “Early on FSF in Shar-Pei was hypothesized to be an animal model for Familial Mediterranean Fever in humans. Recent work indicates this is not true, although FSF is very similar to FMF in man.”

About Familial Shar-Pei Fever

FSF usually starts before 18 months of age (that’s about age 15 to 20 in human years), but symptoms can start at any age. Flares can be triggered by stress, training sessions, dog shows, illness, and for females, coming into heat (Canine Estrus- the fertile period for dogs).

In FSF, fevers last 12 to 36 hours and come with other symptoms. Fevers regularly reach 105 to 107 degrees F, which is considered dangerously high in dogs. All these symptoms vanish with the end of the fever.

Other symptoms that can occur with an FSF flare include:

- Joint swelling – particularly the ankle joints. This is the most common symptom besides the fever, also giving the condition the name swollen hock syndrome (SHS). Sometimes the wrist joint will swell.

- Lips/muzzle swelling

- Lethargy

- Lack of appetite

- Inflammation inside the ear

- Cutaneous mucinosis – This is a buildup of mucin (a fluid) under the skin.

- Excessive thirst and urine

- Abdominal pain

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

Other Conditions Noted with Dogs with SPAID, with or without Fever:

- Arthritis

- Recurrent otitis

- Mast cell disease

- Cellutis

- Swollen hocks

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Lymphangitis

- Lymphedema

- Lymphangectasia

Rare Complications

- Immune-mediated vasculitis that may include pustular dermatosis and sloughing of the skin.

- Amyloidosis – 5% will develop renal failure. Some Shar-Pei dogs will get amyloidosis without having symptoms of a fever syndrome. This can happen in FMF type 2 in humans.

- Liver amyloidosis

- Increased risk for blood clots

- Increased risk for other kidney diseases

Characteristic Blood Test Results During a FSF Fever Include:

- Increase neutrophils (in some cases low neutrophil counts are also possible)

- Increased monocytes

- Increased WBC

- Elevated ALP or other liver function tests

- High cholesterol

- Hyperglobulinemia

- Elevated bilirubin

Treatment for Shar-Pei Fever Syndrome

“All Shar-Pei with FSF should be on colchicine, and be regularly monitored via urine samples and blood work for development of complications,” states Jeff Vidt, DVM. Dogs on colchicine have fewer flares, but still need on demand treatment for the break through flares. Usually NSAIDS are given for treatment during flares.

Why Do Some Shar-Peis Get FSF?

The “why” is found in the genes. Two pathways lead to an increase of inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β levels in FSF. One of the pathways involves the NLRP3 inflammasome and the other involves toll-like receptors TLR2 and TLR4. The NLRP3 pathway is involved in a few human autoinflammatory diseases, such as cryopyrin associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), while TLR4 and TLR2 are involved in other inflammatory conditions, such as ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and kidney disease. TLR2 and RLR4 have also been indicated as possibly being involved in the autoinflammatory disease, mevalonate kinase deficiency (hyper-IgD syndrome [HIDS]). Shar-Peis with FSF also have increased IL-6 levels.

FSF has been known to be a genetic autoinflammatory disease for several years, but a genetic test for it just became available in 2016. The gene responsible, the HAS2 gene, is the same one that creates the signature wrinkled look of the Shar-Pei. Every Shar-Pei has a mutation on or near HAS2 that creates more hyaluronan. This is a protein found in different parts of the body, including cartilage and skin. Shar-Peis have excessive hyaluronan, which creates the wrinkled skin.

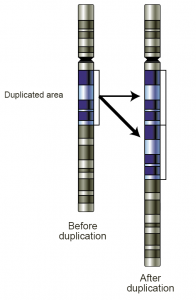

What has been learned is that mutations that produce a lot of wrinkles lead to FSF. Dogs with fewer wrinkles do not get FSF. In FSF, duplications on the gene, rather than missense mutations, lead to increased hyaluronan. The more duplications, the higher the chance the dog will develop FSF.

According to Dr. Vidt, it’s the breakdown of the hyaluronan that activates the inflammation. He states, “Low-molecular weight break down products of hyaluronan metabolism are pro-inflammatory and exacerbate the pro-inflammatory process involved in FSF.”

What Can the Shar-Pei Dog Teach Us?

What Can the Shar-Pei Dog Teach Us?

It is possible that this research and understanding of this rare canine genetic fever syndrome will one day bring new insight into human fever syndromes. Although located on a different chromosome, humans do have a HAS2 gene. According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, “Changes in the serum concentration of HA are associated with inflammatory and degenerative arthropathies such as rheumatoid arthritis.” However, these Shar-Pei FSF studies are the first to connect HAS2 and hyaluronan with a fever syndrome.

The authors of the HAS2 study state, “This study suggests that HAS2 dysregulation can trigger a periodic fever syndrome in dogs and therefore it will be relevant to examine the approximately 60% of human fever patients who currently have unexplained disease.”

Further, Lindblad-Toh, one of the study’s authors, reports in an interview for HealthCanal, “The Shar-Pei dog is a great model for human periodic fever syndromes,” she says. Currently, finding regulatory mutations in human disease is difficult. “In humans, we are still focusing on the protein-coding genes themselves, where the mutations are more easily understood,” she explains. “But finding these types of mutations is easier in the purebred dog since regulatory mutations are common.”

If the real thing isn’t in your future, this cute Shar Pei Beanie Baby could be your perfect companion.

About the Shar-Pei Breed

This breed not only can have a rare genetic disease, they are also considered a rare breed. So if you are looking for a true furry companion, a Shar Pai may be just the friend you need. Just know that he might need extra care than your average pet. It’s estimated that 20 to 30 percent of purebred Shar-Pei dogs have FSF/SPAID. Adults grow to be about 45 to 60 pounds, and are described as being independent, loyal, calm, intelligent, and strong-willed. Due to their history as a fighting dog, some may not to get along easily with other dogs. How good they are with children varies from dog to dog.

Or maybe this cute Shar Pei Beanie Baby will make the perfect pet for you.

Fun Fact: The Chinese once believed that the Shar-Pei dogs’ black mouth would scare off evil spirits.

References

- Royal Shar-Pei: Shar-Pei Fever & Familial Amyloidosis

- Dr. Jeff Vidt: Familial Shar-Pei Fever

- Mar Vista Animal Medical Center: Shar-Pei Recurrent Fever Syndrome

- Arthritis Research & Therapy: Toll-like receptors and NOD-like receptors in rheumatic diseases

- Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension: Toll-like receptors in kidney disease

- Dr. Jeff Vidt: SPAID – Shar-Pei Autoinflammatory Disorder

- HealthCanal: Hyaluronic acid regulatory gene linked to periodic fevers

- PLOS Genetics: A Novel Unstable Duplication Upstream of HAS2 Predisposes to a Breed-Defining Skin Phenotype and a Periodic Fever Syndrome in Chinese Shar-Pei Dogs

- American Kennel Club: Chinese Shar-Pei

- PubMed.gov: TLR2/TLR4-dependent exaggerated cytokine production in hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D and periodic fever syndrome

- Phys.org: A genetic test for Shar-pei autoinflammatory disease

- Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine: New test for Shar-Pei breed: Cornell’s AHDC first in nation to provide the diagnostic

- National Center for Biotechnology Information: HAS2

Photo Credits

- “Gene-duplication” by Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute. The image was brought here from enwiki en:Image:Gene-duplication.png. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Black Shar_Pei reading by vitalytitov/BigStockPhoto.com

- Top tan Shar-Pei by Willee Cole/BigStockPhoto.com