The periodic fever syndromes fall into the autoinflammatory disease category. These conditions include familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), cryopyrin associated periodic syndrome (CAPS), hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome (HIDS), TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), and several other chronic diseases that have recurring fevers and inflammation as the main symptoms. As researchers learn more about these conditions, more diseases that were once thought to be autoimmune are now being considered autoinflammatory. Recent research has placed some diseases that were previously known as autoimmune diseases, such as systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA, also known as soJIA), Sweet’s syndrome, and Behçet’s disease, into the autoinflammatory category or as having autoinflammatory components.

The periodic fever syndromes fall into the autoinflammatory disease category. These conditions include familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), cryopyrin associated periodic syndrome (CAPS), hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome (HIDS), TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), and several other chronic diseases that have recurring fevers and inflammation as the main symptoms. As researchers learn more about these conditions, more diseases that were once thought to be autoimmune are now being considered autoinflammatory. Recent research has placed some diseases that were previously known as autoimmune diseases, such as systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA, also known as soJIA), Sweet’s syndrome, and Behçet’s disease, into the autoinflammatory category or as having autoinflammatory components.

But what’s the difference between autoimmune diseases and autoinflammatory diseases? And does it matter?

| The Cliff Notes |

|---|

| Autoinflammatory = Malfunction in the Innate Immune System |

| Autoimmune = Malfunction in the Adaptive Immune System |

Both autoinmmune and autoinflammatory diseases do have an immune system malfunction as the underlying cause of the symptoms. And both share some of the same symptoms, such as joint pain and swelling, rash, and fatigue. However, the underlying cause or mechanism of the diseases are different. This difference affects treatment options, long-term health risks, and possible complications from the systemic inflammation.

The Acquired Immune System and the Innate Immune System

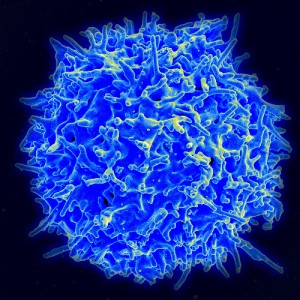

There are two main parts to the immune system, the acquired, or adaptive immune system, and the innate immune system. The acquired immune system learns throughout a person’s life what pathogens to attack. Once exposed to a pathogen, such as a flu virus, the acquired immune system learns from it and remembers it. When encountered again, it makes antibodies to attack it. Targets of the adaptive immune system are specific.

The body’s innate immune system is more primitive, according to the National Institutes of Health. The innate immune system uses white blood cells and acute inflammation to attack pathogens. The innate immune system may be activated by triggers, but in some autoinflammatory diseases, the genetic mutation causing the disease makes certain danger sensors (known as NLRs, NOD-like receptors) in cells to become frequently, or even continuously activated. These activated molecules in the cell join with other molecules to form an inflammasome that coordinates a strong innate immune system response. Fever is a primary symptom of an activated innate immune system. This chronic activation of the innate immune system can lead to systemic inflammation that occurs throughout the body.

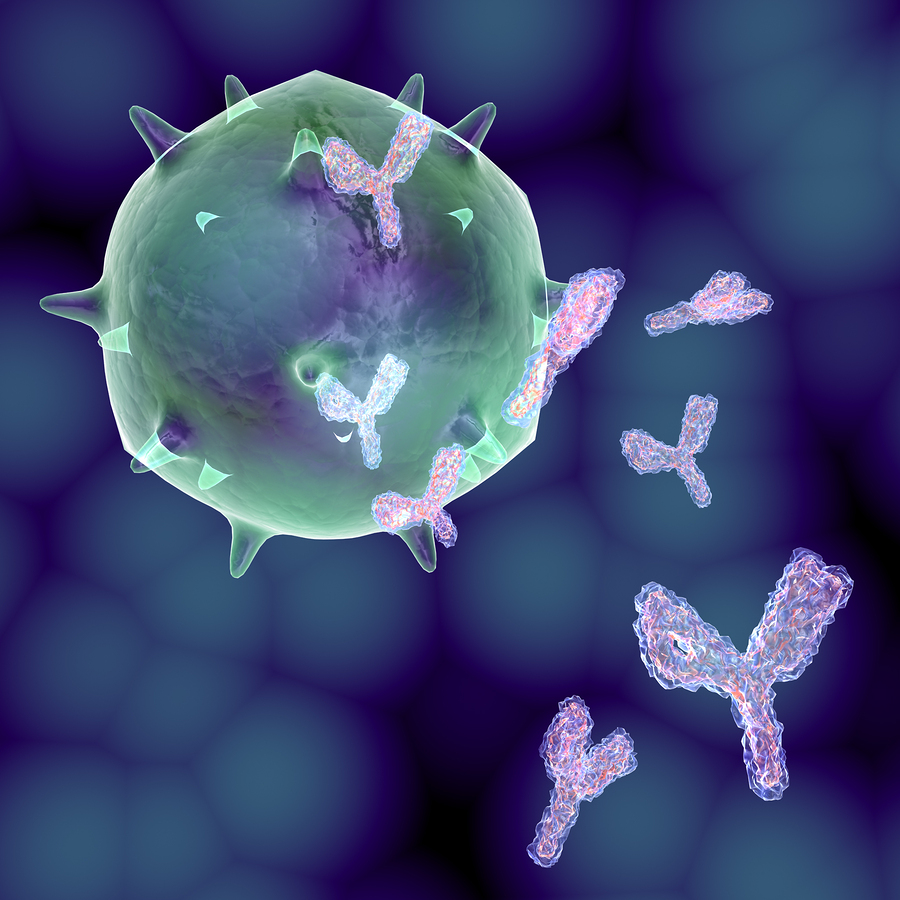

In autoimmune diseases, the adaptive immune system produces antibodies that target and attack specific parts of the body. pseudolongino/Bigstockphoto.com

Autoimmune Diseases – A Dysfunction in the Adaptive or Acquired Immune System

In short, in autoimmune diseases, the adaptive or acquired part of the immune system has mistakenly identified something specific in the body as harmful and attacks it causing symptoms. The initial inflammation occurs mostly at the location in the body that the autoantibodies are targeting, but it can progress to other parts of the body.

Normally an immune system’s white blood cells produce antibodies to attack illnesses that would harm the body. The targets of these antibodies include viruses, bacteria, parasites, and even cancer cells. In autoimmune diseases, the body produces antibodies that essentially attack different parts of the body. For example in Grave’s disease, the body produces antibodies that target the thyroid causing the thyroid to produce too much hormone. In rheumatoid arthritis, the antibodies attack the lining surrounding the joints causing inflammation. Allergies are also considered an autoimmune disorder because the body is attacking substances that it should ignore, the proteins of plant pollens or certain foods.

In some cases, once these antibodies become active the innate immune system may also become active, causing inflammation throughout the body in response to the antibodies fighting off a perceived infection. This innate immune system acts as back up to fight off the infection.

Autoimmune diseases overall are rather common, affecting about 23.5 million Americans according to WomensHealth.gov. Some individual autoimmune diseases are quite rare while others are considered common. The causes of autoimmune diseases can vary. Some are hereditary, some are triggered by another illness or environmental factors, and some are caused by a combination of factors. More women than men are affected by autoimmune conditions.

Because autoimmune conditions are common, there is more research, knowledge, and medications available to treat these conditions.

In autoinflammatory diseases, the innate immune systems reacts often without cause. A primary tool of the innate immune system is fever. AlexWhite/Bigstockphoto.com

Autoinflammatory Diseases – A Dysfunction of the Innate Immune System

In short, in systemic autoinflammatory diseases, the innate part of the immune systems reacts often without cause and without control. Sometimes there may be an injury or a real virus or other pathogen that triggers the innate immune system, but the reaction is not well controlled and is over reactive. The inflammation is often general and not targeted to one area of the body, meaning that from the start, the inflammation can occur anywhere in the body and is not limited to a specific region. Fever, being one tool of the innate immune system to fight infection, becomes the most common symptom of many systemic autoinflammatory diseases. Muscles, joints, skin, the gastrointestinal system, and internal organs, can also all be affected by this inflammation simultaneously.

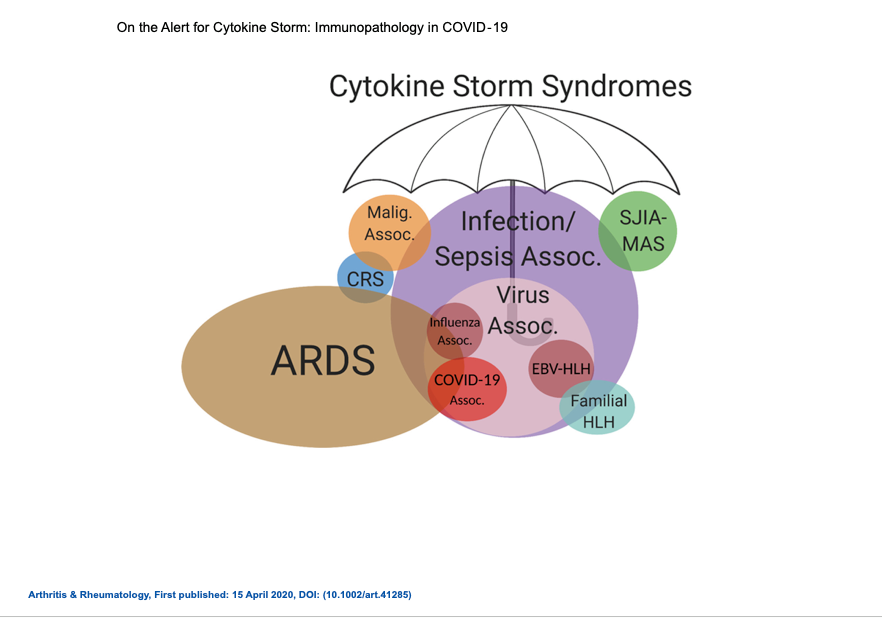

Because it’s the innate immune system that overreacts first, not the acquired or adaptive immune system, in most patients with autoinflammatory conditions, diagnostic autoantibody tests are usually negative. The innate immune system is reacting without antibodies to trigger it. In autoinflammatory conditions, the genetic mutation causing disease leads to activation of the innate immune system, leading to the dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 and TNF-alpha and others that are over produced, rather than autoantibodies driving the inflammation.

Many autoinflammatory diseases have been identified as being caused by genetic mutations. A mis-spelling is another term for this sort of mutation, since some of the autosomal dominant hereditary autoinflammatory diseases (such as CAPS) are due to one amino acid in the DNA taking the place of the standard amino acid for that area of the genetic code. Genetic tests are now available to help to aid in the diagnosis for a number of autoinflammatory diseases, but there still can be mutation-negative cases with full clinical symptoms of the disease, so genetic testing is just one tool in the diagnostic process. With the autosomal dominance of some of these diseases, the mutation occurred somewhere in the family lineage, so patients may have a parent and grandparents with the same condition.

However, some patients may also have an autosomal dominant mutation that happened spontaneously, at some point in their conception, or in the first cells in a fertilized egg. Some diseases follow an autosomal recessive inheritance, where each parent must pass on the mutation to cause disease. In recessive conditions, rarely does a family history include that disease, except in some diseases like familial Mediterranean fever that the recessive trait is carried in the DNA of 1 out of 5 people from certain ethnicities. In some cases, the genetics are not that simple or completely understood.

Autoinflammatory conditions are very rare diseases. The most common is thought to be periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) but there are more rare ones, such as CANDLE syndrome, are only identified in a handful of patients around the world. Because of the rarity of these conditions, knowledge is usually limited about these diseases, and so are treatment options. They can be more difficult to diagnose because the long list of symptoms may seem at first to be unrelated. For example, in Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS)–a form of CAPS, doctors and patients may not recognize that hearing problems, recurring fever, and skin rashes are part of the same syndrome.

Why Does the Difference Matter?

To the patients who suffer from very similar symptoms, such as inflamed and painful joints, the differences of autoinflammatory vs. autoimmune may not matter to them. They all want and need good treatment. However, the common treatments for autoimmune conditions may not work well for autoinflammatory conditions because the cause is different. To best treat each condition, researchers need to understand the cause and target that specific mechanism of the innate immune system that is overactive to help develop the best treatment. Even amongst the different systemic autoinflammatory diseases, different treatments work best for different fever syndromes because different parts of the innate immune system are overactive or not controlled. While interleukin-1ß inhibitors may work very well in some fever syndromes, TNF inhibitors work better in others; but for other conditions, neither of these types of drugs may be the best choice. Also, understanding the basic mechanisms of autoinflammatory diseases helps researchers and patients understand possible complications of the disease that may differ from autoimmune conditions.

The Autoinflammatory Alliance is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization dedicated to helping those with autoinflammatory diseases.

Donate now to help with awareness, education, and research for these rare diseases.

*Healthy T-cell photo by NIAID, Flickr

References

- National Institutes of Health: Understanding Autoinflammatory Diseases

- Dermnet NZ: Autoinflammatory syndromes

- MedlinePlus: Autoimmune disorders

- WomensHealth.gov: Autoimmune diseases fact sheet

- University of South Carolina School of Medicine: Innate (non-Specific) Immunity

- U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health: Autoinflammatory syndromes: diagnosis and management

- PubMed.gov: Autoinflammatory syndromes

- Science Direct: Autoinflammation and autoimmunity: Bridging the divide

- Immune Regulation Research Group, and Immunology Research Centre, School of Biochemistry and Immunology, Trinity College Dublin 2, Ireland: IL-1 – Master mediator or initiator of inflammation

- European PubMed Central: Horror autoinflammaticus: the molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease

- National Institutes of Health: Periodic fever syndrome and autoinflammatory diseases

- National Institutes of Health: Immunology in clinic review series; focus on autoinflammatory diseases: update on monogenic autoinflammatory diseases: the role of interleukin (IL)-1 and an emerging role for cytokines beyond IL-1

- The Autoinflammatory Alliance: CAPS: Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndromes

- Learning About Familial Mediterranean Fever

- The inflammasome-A Linebacker of innate defense

- Inflammasome and innate immune system discussion from the Autoinflammatory Alliance CAPS guidebook, written by leading experts.

- NOD-like Receptors Review

- Periodic Fever: A Review on Clinical, Management and Guideline for Iranian Patients – Part II

- Expression of cytokines, chemokines and other effector molecules in two prototypic autoinflammatory skin diseases, pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome.

- Amyloidosis Patient Information Site: The inherited periodic fever syndromes – general information

- Hindawi: Systemic Arthritis in Children: A Review of Clinical Presentation and Treatment